Author: OrientExpress

“There is no thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives,” poet, author, and activist Audre Lorde declared in her famous 1982 speech at Harvard University, referring to necessary alliances between struggles against sexism, racism, classism, and other forms of inequality. A few years later, U.S. lawyer Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality, which she used to capture the interwoven nature of power relations. She used it to clarify that Black women experience discrimination that they do not share with Black men or white women and cannot be reduced to either racism or sexism. She derived the concept of intersectionality, which in this context means intersection, as follows:

Let’s take as an example a road intersection where traffic comes from all four directions. Like this traffic, discrimination can be multi-directional. When an accident occurs at an intersection, it may have been caused by traffic from any direction – sometimes even traffic from all directions at once. Similarly, if a Black woman is injured at an “intersection,” the cause could be both sexist and racial discrimination.

-Kimberlé Crenshaw

The recognition of mutual overlaps of power relations requires complex and differentiated analyses and counterstrategies. On the following pages, a brief presentation of three Erasmus+ projects will focus on possible intersectional perspectives in adult education. The learning center of the Viennese association Orient Express – Counselling, Educational and Cultural Initiative for Women, which is involved as a project partner and has many years of experience in the field of basic education with educationally disadvantaged women.

Participants in basic education are usually affected by multiple discriminations (educational disadvantages, low economic resources, possibly precarious residence permits, experiences of racism, etc.), which mutually reinforce each other. In addition, many people have experienced war and displacement in the recent past, which can have a negative impact on their mental and physical health.

Regarding this background, the question arises for adult education institutions working with persons with multiple disabilities, how the educational opportunities of persons in need of basic education can be improved through intersectional analyses and approaches. In this context, an emancipatory understanding of education is crucial, which prioritizes the Interests, the well-being, an autonomous learning access, the resources and needs of the participants in the foreground.

Intersectionality: When Different Experiences of Discrimination Collide with Each Other

Of the three projects described below, EquALL(ING): EquALL(ING): Equality in Adult Education Lifelong Learning (Intersectionality and Gender) deals most directly with the concept of intersectionality. The two-year Erasmus+ project focuses on Intersectionality of discrimination. While intersectional theories and practices usually focus on gender, race and class together, other social categories such as age, sexuality, dis/abilty etc. are increasingly being considered.

EquALL(ING) aims to share experiences in the field of gender equity at the European level and to formulate proposals on how to analyse and combat these interwoven disadvantages in adult education. In the coming months, it will aim to evaluate the competence of adult educators in the field of gender equality and intersectionality also to elaborate training approaches.

In the first phase of the project, discussion-rounds were held (in Arabic or Dari in our learning center). From the experience of a feminist association, some all too familiar facts were confirmed: Women currently continue to have fewer educational opportunities globally than men. The probability of a (good) school education is further reduced by economic disadvantages in the family. Care responsibilities for children and family members, as well as household chores, severely limit the time and energy that women could invest in their education. If a woman decides to immigrate – for whatever reason – or is forced to flee as a result of war or persecution, she may face structural discrimination and racism in her new place of residence. An odyssey of official channels, official hurdles, insults and verbal abuse as well as justified worries about her own future and that of any children have a detrimental effect on the learning situation – anyone who is mentally preoccupied with securing the immediate necessities of life cannot prioritize learning for perfectly understandable reasons. If the ability to concentrate is additionally limited by learning difficulties, which could have been triggered by a variety of factors, such as massive educational disadvantage, negative school experiences, cognitive factors, but also by violent experiences such as war, displacement or trauma, it could result in the postponement of for example language tests which are in fact obligatory for many of them.

Furthermore, through the intersectional questions in the discussion rounds, we learned that some of the older women who were interviewed felt embarrassed by younger participants, in view of their occasional faster learning successes. In spite of the recognition that lifelong learning goals can be achieved, it can be observed that the aspect of age also plays a certain role in social learning environments.

Although learning processes can demand great effort from educationally disadvantaged people, especially in the context of insecure life circumstances, many of the participants expressed their voluntary commitment and appreciation of education and told us that they would like to have more everyday communication with people in German – statements that clearly disagree with the prevailing stereotypical discourses of “unwillingness to learn” and “refusal to integrate” among the participants*.

While the project aims to identify commonalities regarding (shared) experiences of marginalization. It also suggests principles and guidelines for adult education which are derived from these commonalities. However, this must not amount to generalizations. Neither “women” nor “migrants” nor “educationally disadvantaged women with an immigration history” form a uniform group about their needs and wishes for a successful educational path. In each individual person, experiences and resources are bundled in an individual way.

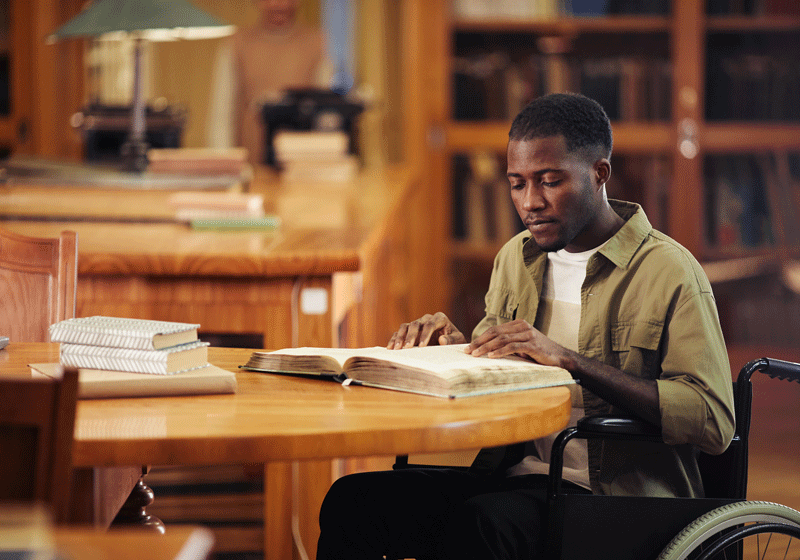

Accessibility in basic/primary education from the perspective of disability studies

While factors such as gender, race, class, and nationality have long been the focus of attention in intersectional approaches, disability has only recently been included as a marginalizing feature. Indeed, people with disabilities face multiple risks, such as financial disadvantage, unemployment, and social exclusion, due to their limited participation in the formal and non-formal education system. Thus, adult education could be an important resource to increase the skills and quality of life of people with disabilities. Nevertheless only 10% of them take advantage of lifelong learning opportunities, which is half the participation rate of the general population at the EU level (Eurostat 2018). On closer inspection, this is also not at all surprising, as persons with disabilities face multiple organizational and spatial barriers.

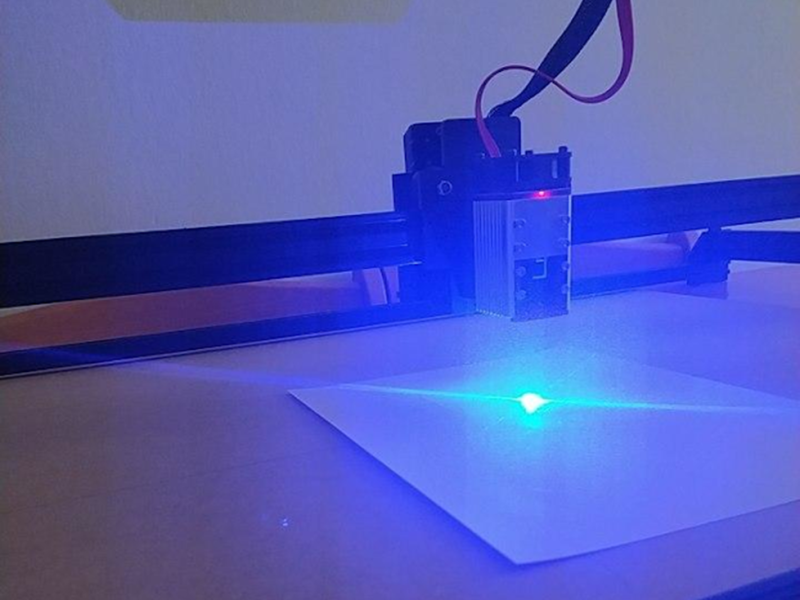

In this aspect, the project IEDA: Inclusive education: ensuring participation of persons with disabilities in non-formal adult education addresses the causes and consequences of these barriers in the field of non-formal adult education. on the one hand, the consortium is composed of organizations working in the guidance and counselling of persons with disabilities or in the development of assistive technology (AT), and on the other hand it consists of adult education providers trained in the inclusion of persons with disabilities.

The barriers that people with disabilities face in adult education institutions are as diverse and varied as there are forms of disability. They range from premises that are either not or just partially accessible for people in wheelchairs or with visual impairments (lack of signage in Braille), to a lack of competence and sensitization of adult educators, to the lack of utilization of assistive technology (AT). Assistive technology (AT) includes technical tools designed to facilitate the participation of people with disabilities in communication processes – i.e., hardware or software such as text-to-speech converters, computer peripherals adapted for people with physical disabilities, induction loops that facilitate indoor communication for people with hearing disabilities, and more.

By participating in this project, the Orient Express association aims to expand its competence in terms of target group-specific educational offers and to increase the proportion of people with disabilities in basic education in the long term. At the same time, from our point of view as a migrant organization, this raises the question of future approaches to support people who are, for example, visually- or hearing-impaired and did not grow up in a German-speaking environment. How can people with no or little school education be supported in their educational process, who may not have had the opportunity to learn sign language or Braille? What competencies do trainers in adult education and specifically in basic education need in order to consider these intersections of experiences of discrimination and what alliances are needed to help shape innovative approaches here?

While the project aims at the inclusion of people with disabilities in basic education in the short and long term, the inclusion of perspectives from disability studies – which have already become apparent three quarters of a year after the start of the project – goes far beyond this in the long term and is able to think more broadly about accessibility and inclusion in basic education and to provide important insights regarding participant-centeredness in general.

A critical understanding of resilience building

Finally, the last project presented here, RESET: Building Resilience in Basic Education, addresses the issues of resilience building and self-care in basic education.

By defining resilience as a key competence in basic education, the project aims to broaden the activity scope of educators as well as participants according to their personal needs. The crucial question was how people with experiences of violence, intersectional discrimination and trauma (which are often related to experiences of war and displacement) can find a safe place in basic education where they feel comfortable and can develop autonomous and self-determined learning strategies for themselves and can experience self-efficacy. Approaches and methods in this regard build on the existing resources and not on the supposed deficits of learners.

However, the focus is on a critical approach to the concept of resilience, which is currently on everyone’s lips. Against the backdrop of intersectional discrimination, it must be clear that resilience does not mean accepting untenable conditions and adapting to them, but rather an appreciative attitude towards oneself and others, the strengthening of existing resources, self-determined learning processes and the development of a safe working atmosphere.

First and second language learners were deliberately targeted together with trainers. Thus, self-care practices are not only aimed at participants but also at basic trainers. In a virtual training we exchanged approaches and exercises in the field of self-care with about twenty course instructors from Germany, Italy, Austria and Greece. For those who want to remain committed, capable of relating and regulating in the often-precarious adult education work and who want to be able to convey confidence to participants and offer them a safe space, should consider integrating strategies of demarcation and stress reduction into their personal everyday life.

Summary: Forging Broad Alliances Against Discrimination

Intersectional approaches have shown that social relationships do not emerge and exist in isolation from one another but are interwoven. From the perspective of critical educational work, the question arises as to how the heterogeneous perspectives of persons subjected to multiple discrimination can be reintegrated into the development of approaches and methods. In this context, in educational and further training Programs for basic educators, employment the following Topics could be beneficial.

Practical knowledge about the effectiveness of asymmetrical power relations in society and the educational system; reflection on personal localizations and privileges and/or discriminations and their effects on the activity and self-image as a trainer; elaboration of self-determined learning processes instead of paternalism; orientation towards participants’ resources instead of victimization, and many more. These efforts could envision a space “where different voices can share their realities and be heard, but also an active integration of differences” (Ghai 2002).

Including an intersectional perspective in (adult) education, in any case, means forging alliances between different emancipatory efforts and people, initiatives and organizations that strive for the inclusion of women*, of people with immigration histories, with educational disadvantages, with disabilities, different ages, diverse sexual identities, etc. and creating synergies from the different perspectives.

Literature

Audre Lorde (2021) Sister Outsider »Nicht Unterschiede lähmen uns, sondern Schweigen«. Dt. v. E. Bonné und M. Kraft, Hanser.

Anita Ghai (2002): Disabled Women: An Excluded Agenda of Indian Feminism, in: Hypatia

Vol. 17, No. 3, Feminism and Disability, Part 2, S. 49-66.